Sonic Youth cofounder Thurston Moore not only flies the flag as one of the “Greatest Guitarists” of all time (99th out of 100, mind you), the renegade noisenik is undoubtedly at the top of the tastemaker heap. At Moore’s prodding, DGC, Sonic Youth’s label, inked Nirvana to a record deal and several years before that he was singing the praises of then-unknowns Dinosaur Jr, handpicking those pedal-hopping sludgeheads as an opening act.

Moore’s habit of plucking bands out of obscurity may be best personified in the case of one of the best—and most forward-thinking bands—you’ve probably never heard: Notekillers.

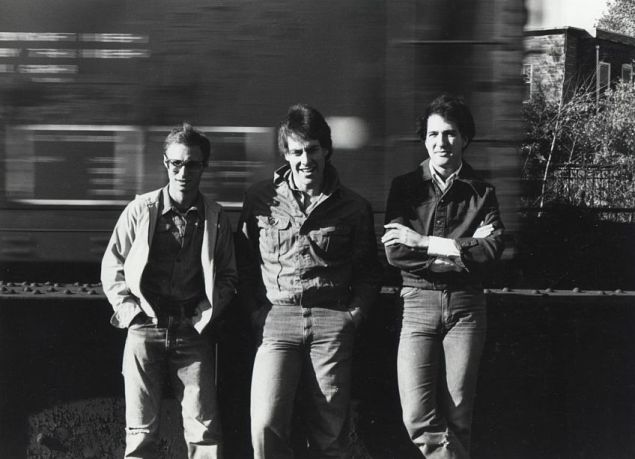

Back in 2001, Moore slapped a Notekillers cut on a mixtape for MOJO magazine, calling them a major influence on Sonic Youth when the NYC art-rock noisemakers were first starting out. Thus, the Philly all-instrumental trio of guitarist David First, bassist Stephen Bilenky and drummer Barry Halkin—birthed in 1977 and gone and forgotten by ‘81—were given a second incarnation (but more on that later).

The track Moore paid homage to was “The Zipper,” and as First said in his introduction before this ear bleeder of an WFMU performance in 2011, “the song that started it all for us.”

“The Zipper” was an anomaly in the punk rock, post-punk and no wave annals when it was released in 1980. An instrumental speedball of skronk-rock riffage, it portended a power trio so ridiculously ahead of its time and proto-everything that Notekillers were the epitome of unclassifiable. They mashed their British rock fandom with DIY punk rock aesthetics, no wave raunch, avant-garde jazz firebreathing and proggy complexities into fist-pumping, stadium-sized anthemry, a lethal blend that was met with audiences—if there were any—unsure what to decipher from this unheard music.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aqPdaTXutdk&w=420&h=315]

Notekillers inevitably disbanded to very little fanfare, wallowing in oblivion until Moore helped trigger their comeback. That resulted in his Ecstatic Peace! label issuing a compilation of their early works (Notekillers 1977-1981) in 2004.

Since then childhood pals First, Bilenky and Halkin have been at the helm of Notekillers’ revival, albeit sporadically. 2010 saw the release of We’re Here To Help, the band’s first set of original material in three decades and six-odd years later, they’ve dropped its follow-up.

Fittingly titled Songs and Jams Vol.1, Notekillers remain an ageless power trio, its sonic din of gnarly licks combining no wave’s nihilism and downtown NYC experimentalism with the fury of ’70s Bowery punk rock. Envision Glenn Branca’s The Ascension thrashed out by the Ramones and you get the idea of their epic, guitar godhead mettle.

While Notekillers were on the back burner for years, First, an NYC mainstay, has been ensconced in the local free-improv scene and as an accomplished minimalist composer. He’s played with Oneida drummer Kid Millions and Liturgy bassist Bernard Gann as Matter Waves and he and Halkin have recently begun to gig as bl0odoolo0ps. His avant leanings are showcased in his ongoing solo acoustic guitar project (via the Brooklyn-based Fabrica label) and on the just-issued The Complete Gramavision Session (1989) by The World Casio Quartet, First’s 1980s microtonal electronics group.

The Observer caught up with the busy First recently over email to talk at length about Notekillers’ beginnings in Philly, the infamous Moore tale, playing with Cecil Taylor revelations and more.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JhrbEpxO44s&w=560&h=315]

Can you recall what the Philly music scene was like when Notekillers first started playing around 1977 and on? What was going on there?

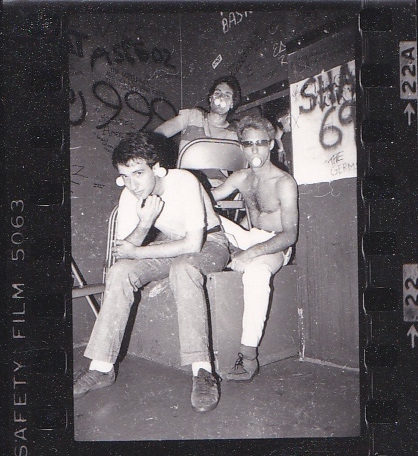

The first, and, by far, most important venue in Philly was called the Hot Club. This was where all the touring bands played—the Cramps, B-52s, Elvis Costello, Dead Kennedys, Dead Boys, Richard Hell, Johnny Thunders, and many others. And, of course, all the local Philly bands, including us, played there as well. The place was owned by a guy named David Carroll—who is definitely a Philadelphia hero.

Were there musicians and bands in Philly at the time who shared similar influences and aesthetics as yours?

Well, not really. Don’t get me wrong—there were some very interesting bands in Philly. The Stickmen, King of Siam, Bunnydrums, Crash Course in Science are a few that I remember who managed to transcend the most obvious stylistic codes of the era. But they all fit in in some way or another and were thus supported—more than we were, anyway. We were just considered weird and not supported at all, to say the least. But, somehow, David Carroll took a liking to us and booked us anyway.

How did you actually hook up with Stephen and Barry to start Notekillers?

Barry, Stephen and I grew up together. Barry is my oldest and best friend since third grade and Stephen is not far behind.

I had a band called Dead Cheese in high school—that included Barry for most of its existence and Stephen for a large chunk of it—which moved through assorted stylistic phases influenced by the psychedelic rock of the era.

After high school I stuck around Philly while they both left town to go to school. During that time I had some new musical adventures including attending Combs College of Music for a time, playing with Cecil Taylor, exploring analog synthesis at Princeton and studying with a legendary jazz theory/guitar teacher named Dennis Sandole who taught John Coltrane amongst many others. When Barry returned, we just naturally started playing together again, but the influences had changed.

Eventually, after a couple of other friends who played bass in Dead Cheese decided this new thing wasn’t for them, Stephen—who was actually a guitarist in Dead Cheese—took up the bass and we were set.

What do you remember about playing with Cecil Taylor?

It was possibly the most intense, electric and, afterwards, somewhat paralyzing experience I ever had. It just pushed every mental, physical, emotional button. I had started playing with Cecil at Glassboro State College in New Jersey where he was an artist-in-residence for a couple of semesters. There were, like, 20 or more of us taking his class, but not one person was actually enrolled at the school, or paid anything, as far as I know—just a bunch of young Philly players who wanted the opportunity to hang out and play with the man.

After a few months, he asked me, and a couple of others to come up to New York to join an ensemble he had already started rehearsing for a concert at Carnegie Hall. The first thing that popped into my head when you asked the question was sitting in front of Sunny Murray onstage at that Carnegie Hall performance. I’d never before or since experienced a kick drum like that. It was like a cannon and it took all I had to keep from jumping out of my seat every time he hit it.

I also vividly remember how my heart leaped after getting a “thumbs up” sign from the great bari sax player Charles Tyler when I finished the one solo I had that night. I felt like I had already gained Cecil’s trust through things he had said to me prior, and, of course, that he had asked me to come up to join the ensemble to begin with, or I wouldn’t have been able to deal with some of the head games that came along with the situation. Not from Cecil, but from some of the other younger players—including a guitarist who was there before me and clearly didn’t relish sharing the role.

“I wanted to create rock music that wasn’t about anything, but was focused as much as possible on the phenomenological energy of sound itself.”

At any rate, it meant a lot to receive the approval, in that moment, from someone like Charles. But possibly the thing that made the biggest impression on me was, this was a large ensemble—over 30 people—half the players were some of the greatest and most revered players in the music at the time and half were kids like me. The piece we were doing had been developed and rehearsed for months—it was very much composed. And yet, before we went on, after our sound check and clearly after there was barely any way to adjust, Cecil told us he wanted us to completely reverse the order of the sections that made up the piece. That blew my mind!

But during all this I was 20 years old and still living in Philly. I’d left school after less than two years to study full-time with Dennis Sandole. Then I left Dennis to fully commit to commuting to New York City and being part of Cecil’s ensemble. After that ended I felt kind of lost. It was a huge withdrawal from such a crazy high. I didn’t feel emotionally prepared to dive back in by moving to NYC full-time. Nor was I at all sure I wanted to. Part of me felt like I’d experienced the best of that music possible. So, I spent the next couple of years not playing with anyone.

I had bought a classical guitar with the money I got from the Carnegie Hall performance and all I did was play it every morning as kind of a ritual meditation on all I had been through. Then, on a whim, I jumped into the Princeton electronic music classes, which led to my teacher there, Michael Dellaira, arranging for me to have pretty much carte blanche access to their analog music studio. During that time, Barry came back to town. I really loved the electronic music stuff and I came very close to going back to school and pursuing it as a musical path. But once Barry and I started playing I put that idea aside and didn’t do anything with electronics for another 10 years.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GEzbMSoB2Is&w=420&h=315]

What were you guys actually listening to or influenced by that helped steer you into what you played in the Notekillers?

Without a doubt, hearing the Ramones—and soon after, the Sex Pistols—made something click. But possibly it was an inspiration more than anything else because I would say that people like Phillip Glass, Steve Reich and John Fahey had just as much, if not more, of an influence on our formal structures. As did the jazz chord-melody structures I explored with Dennis Sandole. And Cecil, Albert Ayler and other free jazz avatars definitely showed me how to heat up those structures till they combusted.

But in certain ways, some of my original heroes had never really left me—I can still point out the Who/Jefferson Airplane/Yardbirds/Kinks tropes in our songs. Another, possibly surprising influence was funk. In the mid-70s I was listening to a lot of early pre-pop Kool and the Gang, James Brown, Earth, Wind and Fire, and, of course all the TSOP/Gamble & Huff stuff. When it comes to guitar, you can’t get more minimalist than funk. I also got massively into reggae.

The whole year I was doing completely abstract electronic music, I was listening to nothing but what is now referred to as “roots reggae” on my car’s eight-track player while driving back and forth to Princeton and anytime I was hanging around my apartment in Philly. I was nuts about it. But, yeah, hearing the Ramones and learning that there was something going on—places to play where new electric guitar bands were creating a scene—was significant. Made me think there might be a way of bringing it all back home, as somebody once said.

[bandcamp width=100% height=120 album=3199848581 size=large bgcol=ffffff linkcol=0687f5 tracklist=false artwork=small]Being all-instrumental had to be a truly original concept back then. How did you arrive at it?

It just seemed like a natural extension of what I had been listening to, and playing in the years prior to our forming. Even with the music during the psychedelic era, the real action seemed to occur after the formality of the vocals were out of the way. But when you’re talking about the minimalism and free jazz I totally immersed myself in post-high school, well, lead singers and lyrics seemed beside the point.

I’ve said this before, but I wanted to create a rock music that wasn’t about anything, but was focused as much as possible on the phenomenological energy of sound itself—that’s what had to carry the day. And a front person seemed like a distraction, a fifth wheel that would destroy the purity of my intention.

Did any of you try to sing or have thoughts about bringing in a front-person?

At the very end, when all hope seemed lost, we toyed around with some vocals, but not much came of it.

At what point did you come to NYC to play?

In 1980. We had made our single, “The Zipper”/”Clock Wise,” and we took a trip up to NYC to pepper the record stores with copies. One of the stores was 99—a record/clothes store on 99 McDougal Street in the Village run by Ed Bahlman. Ed is another hero in our story—as well as in many other peoples’, of course. Ed called us up and asked if we wanted to play up here. We opened up for Glenn Branca at Hurrah. This was one of his first guitar ensembles, I believe, and it was pretty awesome. Ed was also the one who played our single for Thurston and others, though it took me a long time to find out about that!

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8B4r2aNzwz4&w=560&h=315]

Did you think, considering the punk scene happening in NYC, that there would be an audience here for Notekillers at clubs like CB’s than there was in Philly? Did you have high hopes that you’d be better received here?

Yeah, we hoped, but in all honesty, we didn’t find things to be much different for us. What we did find were a few more people who heard something in our sound. The single got very nice reviews in The Village Voice and Trouser Press, and our show at Hurrah was also reviewed very favorably by a writer for NY Rocker. That was most encouraging, but otherwise we saw very little evidence that we were connecting in any kind of meaningful way with audiences themselves in New York.

Any Notekillers gigs here in NYC that stand out in your mind?

Well, there was the time we did a show with the Feelies at a place called the Rock Lounge where people threw things at us. There was a show—our very last show back then—at Maxwell’s where whenever we stopped there was dead silence…it was a room full of statues. Those are the two that stand out. And yet, this is the place I headed to as soon as we broke up [laughs].

You guys eventually called it quits in ’81. Why do you think the world wasn’t ready for Notekillers back then? I would think you would have fit into the no wave movement? Or being in Philly, did you feel detached from that NYC-based scene?

I really don’t know how to answer that. Honestly, I’m not really sure how we fit into the no wave thing. If it existed, we certainly didn’t know about it when Barry and I first started our experiments in 1976. I think there are some common roots for sure, but, well, by the time the Notekillers were officially underway, I had been playing guitar for, like, 12 years and had already been through all kinds of musical eras—including the, much discredited at the time, psychedelic era.

I had studied guitar, for god’s sake—with a master teacher! Whereas, as far as I can tell, an important part of no wave was the idea that you could just start playing from zero and figure it out as you went along. A lot of artists from other disciplines—including visual artists—were doing it. Which is awesome, and obviously led to many new ideas for a lot of people, and broke down even more barriers than perhaps even punk rock did. But it had no real influence on me or the Notekillers. If anything, most of it was more harmonically advanced than our stuff.

We shared a bill with DNA once in Philly and compared to them we sounded like “classic rock.” Which is pretty much the case—I’m a rock & roll musician and I’ve very rarely called myself anything else. I also think our intensity came from a different place. I think, in general, we were actually kind of lousy punks.

If you came to the house we lived in in Philly, you’d be just as likely to hear Joni Mitchell, the Airplane, John Fahey, Bartok, Coltrane, Indian ragas, or Dylan, as much as the Clash, Gang of Four, PIL or the Ramones. We loved it all. I know that sounds completely normal today, but at the time, it was another thing that made us just slightly off-axis from the punk zeitgeist. But where else could we play except the punk clubs? The actual classic rock establishments would not have gone near us.

Over the subsequent 30-year period where Notekillers were broken up, did you keep in touch with Stephen and Barry?

Barry and I stayed in touch and would see each other maybe once, twice a year. Not so much Stephen, whose life took a different path for a few years there. But to his credit, Stephen was right there when the time came and was probably the first to declare he was ready to go.

I know you’ve talked about this before because it’s become stuff of Notekillers legend but Thurston Moore played a role in the band’s comeback, putting out the compilation on Ecstatic Peace! and then later on the reunion of the band. How did you find out that Thurston name dropped Notekillers in MOJO magazine and how floored were you?

A friend/fan from back in the day (all our fans tended to become friends) called Barry and told him that he’d seen an article somewhere in which Thurston mentioned us. Either the guy didn’t remember which magazine, or Barry didn’t. I actually thought that somebody got something wrong—it was a bit unbelievable.

At any rate, it fell to me to write to Thurston and ask the ridiculous question, “Did you mention the Notekillers in an article somewhere?” Luckily, the answer came back, “yes.” I’d say we were both floored. He knew some of my subsequent work, but had no idea all these years that I was in that band. I really didn’t talk about Notekillers much, if ever, once I left Philly.

Had you heard of any interest in Notekillers from anyone besides Moore over the years? I would think there would be record collector types and musicians into Notekillers for sure.

Over the years, I’ve had people tell me they had our single back then—Ira Kaplan of Yo La Tengo, Glenn Branca. Glenn—who I knew from us both being, more or less, part of the same downtown Manhattan music scene—were having lunch one time in the early ’90s when I told him I was in the Notekillers and he pretty much fell out of his chair.

Other musicians have also become friends, and sometime collaborators, through having discovered the Notekillers at some point—John McIntire of Tortoise, Kid Millions of Oneida, Kyp Malone, Brian Chase, John Schmersal of Brainiac and Enon. Byron Coley mentioned us in Spin magazine—something I didn’t find out about until the internet age. Just recently I found an article online from last year where Alec Empire of Atari Teenage Riot called us an inspiration for him.

And, of course, a whole bunch of music writers have shown that they get it and appreciate it. We’ll never be part of any grand cultural nostalgia for the punk era. But anytime a writer attempts to tweak the historical record to include us, it’s gratifying.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4ufCgfSq6Bw&w=420&h=315]

When you decided to resurrect Notekillers and play again, was there any trepidation to play music again that you made in your early 20s? You’ve obviously gone in different directions in music over the years. Being older and wiser and years of minimalist and drone-based compositions under your belt, how difficult—or easy—was it to “rock out” for lack of a better term, again?

O.K., here’s where I guess I should go into something that I’ve very rarely talked about. The whole time I was doing the Notekillers back then I was having serious hand and wrist problems. They didn’t even have names for it as they do now, like carpal tunnel, RSI, etc. Doctors told me they didn’t see anything and implied I was perhaps a little crazy—which I reckon I was, in fact, but the situation was real. One showed me how to tape myself up with support pads, and that was how I spent the next four years anytime I played. And we rehearsed six nights a week. We were pretty obsessed.

But I was seriously miserable. I was 23 years old and I thought I’d ruined my life. But it would’ve really been all for nothing if I didn’t proceed to carry out the mission—or so it seemed. People were counting on me. I was counting on me. So I played through it all.

But here’s the thing—and probably even the other guys in the band don’t know this—it wasn’t playing the Notekillers songs that originally caused the problems. Thing is, you have to understand that, as crazy as it sounds, the Notekillers was a pop-move for me. And it was, compared to what I was doing both with Barry right before, and the years before that. I was coming from serious, all-out free improv-noise-jazz-whatever. Anything that resembled song structures—verses/choruses/etc. was pop music compared to that. So, as much as I liked the fun and clever aspects of doing it, a part of me felt like I was selling-out, going commercial, abandoning the real musical soul mission I had been on for the four to five years prior, etc.

There was certain ambivalence about the whole trip. Even though what we were doing was totally non-commercial compared to almost anything out there at the time, I wanted to go further out. I began trying to create a series of repeatable, formal, microtonal structures out of bending multiple strings. Which I saw as an honorable way of continuing with what I’d done before the Notekillers, but still something I could do with the Notekillers. I just couldn’t stop myself. I felt I was finished with the techniques that led to the dozen or so tunes I’d created for the band—I knew how that all worked, and was compelled to keep moving forward to what I saw as the next step, even though we hadn’t even played a gig yet.

Problem is, some things aren’t meant to be done—at least by me—and the repetition and basic hand positions it took to solidify the bending ideas into structures took its toll after a couple of weeks and I began feeling strange twinges and weakness. Which I denied to myself for a bit, but eventually I had to accept that I wasn’t meant to go there. So I abandoned that project. But the damage was done and my attention turned to surviving playing with the band that was just getting off the ground. Truth be told, apart from one or two songs, everything else we did back then was written by me before I hurt myself. Ironically, though, one of those songs was “The Zipper”—our single.

Sooo…to answer your question [laughs], I never in a million years thought I would or could do those songs again. And, to be honest, the hand stuff has never really gone away. But I reckon I’ve done the best I could with it all. And when it did come time to think about getting back together, it was definitely with the idea that we may not be able to. Not just me—all of us. It was pretty exhausting music when we were in our early 20s. The fact that we did get back together in 2004 to play even harder, with even more intensity, well…you tell me what to call that…

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nIeaoDL6C5Q&w=420&h=315]

In 2010 you guys put out We’re Here To Help and now five years later Songs & Jams Vol.1 has arrived. What was the process like for you to write the songs for that first post-reunion record as opposed to the new record? Did coming out with a new record a mere five years later then easier for you guys to be able to bang out songs and jams?

Same process for writing the songs…I’d come in with an A & B part—what I guess might be called a verse and chorus—and we’d hash it out. It can take a loooong time till the formula reveals itself that makes a song work. Sometimes months. On the jam side, tracks were defined by strategies and gear implemented—specifically on Stephen’s part. On Ring Mod 2 he used a ring modulator pedal, on Trem 2, a tremolo pedal. Not all that cryptic, right?

How did Shelley Hirsch get involved in contributing vocals to a track on the record? What made you want to include singing for the first time on a Notekillers record?

If we knew Shelley back in 1977 we might’ve had a singer. But I didn’t meet her till I moved to NYC, of course. And even then, it took a while for us to work together. I asked her to sing backup on a track for a solo album of songs I wrote—traditional songs with lyrics—called Universary, which included a lot of other guest artists like Zeena Parkins, Ulrich Krieger, Tom Chiu, the late Roy Campbell, and others. And she, of course, killed it.

This was the last thing I did before all the Notekillers revelations in 2001, so it only seemed natural to see what she would sound like with us. She sat in with us a couple of times during shows and I decided it would be cool to create a more formal, permanent structure with her.

You play fairly often as a solo artist and in free-improv mode. I know you are playing a duo show with Barry as bl0odoolo0ps but will Notekillers be playing gigs or touring in support of Songs & Jams Vol.1?

Well…here’s another story for ya. You know, if you stick around Earth long enough, shit happens. About five years ago, I started having attacks of vertigo. And my left ear would clog up. I’d be walking around sometimes and you’d think I was drunk off my ass. I thought at first it was an ear infection, but it would come and go and eventually I had it checked out.

At first I was diagnosed with Meniere’s Disease, which is a horrible, horrible thing to have. People who have that have their lives totally turned upside down. They could be functioning one minute and on the floor unable to move the next. And it’s degenerative—you eventually go deaf in whatever ear is afflicted. No cure. My lowest point occurred about two and half years ago when I spent a night blacking out, vomiting with the worst nausea ever. It was easily the worst night of my life.

This was a few months after we recorded the “jams” side of the album and only a couple of weeks after our last show. We had been doing this second reincarnation for 10 years. And I just basically told the guys that I needed to take a break. I just couldn’t imagine right then going to Philly week after week for rehearsals, playing till I was ready to collapse and all the rest that went along with doing the Notekillers even when healthy! And I told them that maybe it was going to even take something extra special to tempt me to put it all back together. I really thought it was beyond me—at least for the moment. But I said, meanwhile, let’s get this album out and see what happens.

Then, six months later I saw a Meniere’s specialist and he said that he didn’t think I, in fact, had the disease—he figured I had something on the spectrum, but probably not that. That, as bad as my symptoms were, from time to time, my condition was something lesser—an annoyance, perhaps, but not the horrors I’d been dreading. And, it’s true—I definitely have periods where I don’t hear so well in one ear and I experience strange detached disorientation and dizziness, but I’ve successfully done recording sessions, shows, composed music, even mixed music during all of it.

It takes some of the fun out of things sometimes, but nothing seems to stop me, I reckon. In many ways, it’s been the best, most productive five years of my life. And, yes, I’ve begun playing again with Barry recently and I can honestly say we are doing our best jamming ever. So, who knows? I’ve already caught myself once thinking the Notekillers would never play again. I know better than to say it again.

You’ve been fairly active in the local music/experimental scene these days. You and Barry played Trans-Pecos recently as bl0odoolo0ps and Songs & Jams Vol.1 is certainly a rager. From an outsider perspective, it seems you are pretty healthy. I assume you could pull off playing a Notekillers live gig?

Well, all I can say is that I still feel at, or near, the top of my game. My muses are busy as ever. I just started playing sitar last December and more recently acquired a couple of fantastic Vietnamese instruments that I’ll be digging into soon. There’s a new analog synth album coming out in November and a solo harmonica album after that. But I also just had another birthday. If anybody’s ever thought about coming to see anything I do, don’t sleep too long on it.

Notekillers Songs and Jams Vol.1 is available here via American Bushmen and digitally on Bandcamp.

David First plays solo at Muchmore’s on September 11 with Purgist (on tour from Poland)/Richard Kamerman/Douze/Spoil Ground and bl0odoolo0ps plays The Park Church Co-op (129 Russell St, Greenpoint, Brooklyn)with Sunwatchers and Eugene Chadbourne on October 14.