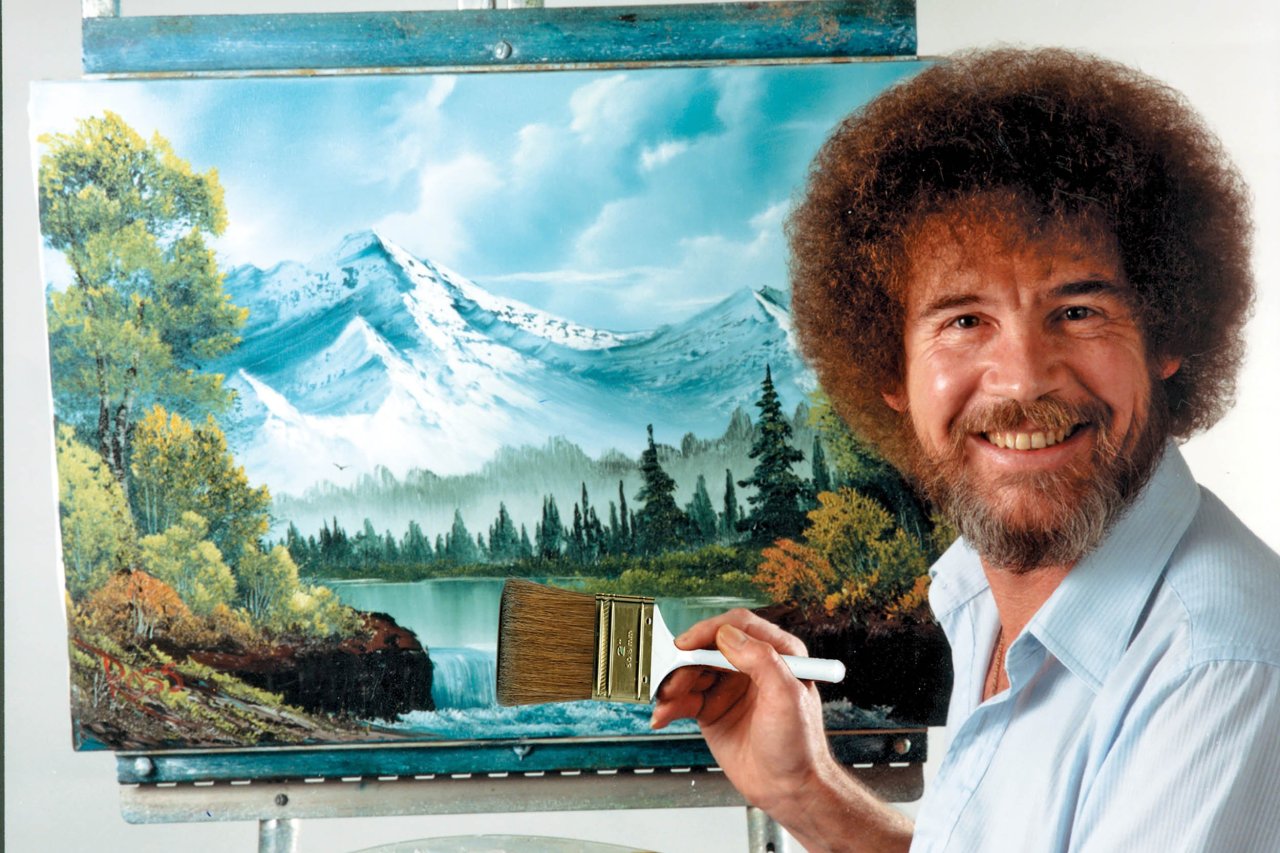

For decades, public television's how-to-paint circuit has been dominated by one person: a gentle, Afro-haired landscape artist named Bob Ross. Through his half-hour show, The Joy of Painting—which originally aired between 1983 and 1994 and is still syndicated today—Ross has taught millions of viewers how to pull "happy clouds" and "happy trees" from their "almighty brushes."

Ross distinguished himself from other local-access artists with his self-love approach to landscapes. "There are no mistakes, only happy accidents," he often said as he painted his tropical beaches and mountain ranges. The approach has worked: By 2001, six years after Ross's death, his show had become a global phenomenon, prompting The New York Times to suggest that he could be "the most recognized painter since Picasso."

The popularity of The Joy of Painting, which began in Muncie, Indiana, and spread to the U.S. and a score of countries, including Canada, Mexico, the U.K., the Netherlands and Japan, has always been something of a mystery. Even at the height of its success, it was always a low-budget production. The audio and video quality of each episode, which featured Ross alone at his easel against a black background, was never great. During the first season, it was so poor that, until his death from lymphoma in 1995, Ross never allowed it to be syndicated.

The 10,000 paintings Ross created in his lifetime are frequently referred to as "kitsch" by art critics who struggle to reconcile the painter's global appeal with his clichéd style. Ross readily admitted his work would "never hang in the Smithsonian," as he once put it to the Orlando Sentinel. But, as he was fond of saying, "if you learned how to make a cloud, your time is not wasted."

It is easy for those who have not seen Ross paint an "Autumn Stream" or the "Grandeur of Summer" to misunderstand the paradox his success presents. There is no question that The Joy of Painting is good—intoxicating, even. Rather, the mystery is what exactly it is that's so undeniably appealing about watching this man paint trees and birds and cabins. As Ross himself said, most people don't watch his show to learn to paint. Instead, they watch it for relaxation, the reclusive painter told the Sentinel in a rare interview in 1990. "We've gotten letters from people who say they sleep better when the show is on."

Whatever the appeal, Ross alone seemed to understand it. According to his longtime backer and business partner, Annette Kowalski, "I can tell you that he did not doubt for one minute that all of this would happen."

Jim Needham, former manager at WIPB, the Muncie television station that launched Ross, tells this story to illustrate the painter's strange magnetism: At the height of Ross's popularity in the U.S., WIPB was approached by a Japanese television company that wanted to syndicate the show. WIPB prepared a sample video for the executives, removing Ross's audio and adding Japanese subtitles. The buyers promptly rejected it, insisting that the painter's voice be reinserted. Even though their audience wouldn't be able to understand a word of what Ross was saying, "they wanted to hear his voice," Needham recalls. "They demanded it." WIPB complied with the request, and, he says, "Japan quickly became our second largest market."

Since Ross's death almost two decades ago, the draw—and with it the mystery—of his voice has persisted. Clips from his shows attract millions of viewers online. A video of Ross painting a mountain, for example, has garnered more than 6 million views on YouTube. One of him painting a quiet pond has 2 million. These videos tend to produce what must be some of the most positive comment sections on the Internet. "Man is his voice melodic. I don't know how the cameraman can stand up by the end of the show," one commenter wrote. "I get knocked out by his voice," wrote another.

Those who watch Ross on YouTube also gravitate toward videos like "Calculator, Writing & Flipping Thick Pages," which is exactly what it says it is: For almost 28 minutes, a soft-spoken woman from the Netherlands named Ilse Blansert writes messages and draws curlicues and hearts in a notebook, and then types nonsense into a TI-83 calculator. It has been viewed 57,085 times.

Other favorites include "Gentleman's Suit Fitting Session" (1,964,105 views), "Virtual Spa: Relaxing Haircut" (2,733,042 views) and "Cranial Nerve Examination Role Play for Tingles, Relaxation, and Sleep" (869,908 views). To call that a partial list is an understatement. There is seemingly no end to these videos of people recording themselves doing what one might fairly describe as absolutely nothing for loyal fan bases that, in some cases, number in the millions.

HAPPY PAINTERS

What unites Bob Ross with all of these videos is a phenomenon known as ASMR. For those who experience it, ASMR is most frequently described as "the tingles" in the head and back that one gets when hearing certain sounds, particularly in the context of some mundane task like being fitted for a suit or learning to paint trees. (But, as just about anyone in the ASMR community will tell you, it is almost impossible to describe to someone who, through bad luck or cosmic misalignment, does not experience the sensation.)

ASMR stands for "autonomous sensory meridian response." It was coined by Jenn Allen, the founder of asmr-research.org, who hoped that legitimizing the phenomenon with a scientific-sounding name would spur research into the subject. But it is, for lack of a better description, completely unscientific: Allen once commented to Vice that she chose meridian because it was a more "polite" synonym for orgasm.

So far, there is no science to support ASMR. But the phenomenon, which boomed on YouTube beginning in 2010, has gotten large enough to warrant coverage byThe New York Times, The Atlantic, Dr. Oz and Oprah Winfrey. A Kickstarter fund-raising campaign for a documentary on ASMR has received more than $15,000 in pledges. If ASMR isn't real, its online community, which numbers in the millions, certainly is. And among the dozen or so creators and consumers of ASMR that Newsweek spoke to, one thing about it is almost universally agreed upon: The lasting, unlikely, appeal of Bob Ross is, at bottom, due to his uncanny ability to induce the ASMR response with every breath and stroke of his brush. As Ilse Blansert, the creator of the calculator video, put it, "If you have one thing in common, 9 out of 10 times it's Bob Ross." Ross, she adds, is often referred to as the "king of ASMR." As a commenter wrote beneath a video of Ross painting a mountain, "Bob Ross [was] the creator of ASMR...without even trying...dayum." The video has more than 6 million views.

The story of how Ross became the king of ASMR begins in the 1940s, with a man named William Alexander. He was a German painter, born in 1918, who practiced the difficult wet-on-wet painting technique in Europe before being drafted into the German army and captured by the Americans during World War II. During captivity, Alexander, who is described by his business partner Laurie Anderson as "sincere and magical," so charmed the soldiers with his painting that he was given special treatment and eventually released.

The rest of his family was not so lucky. "His father, he suspected, was killed by Nazis," says Anderson, who is now the head of Alexander Art. "His mother was killed by TB." One can only imagine that, upon his release from prison, Alexander found himself at something of a crossroads, facing either despair or reinvention. He packed his bags and moved to America, where he eventually turned up, nearly broke, painting half-hour landscapes in an outdoor mall in Los Angeles. In 1974, he was discovered by a local PBS station in Huntington Beach, California, where he began painting landscapes for millions of viewers on his show, The Magic of Oil Painting.

Alexander billed himself as "the Happy Painter" and began showing viewers how to use the wet-on-wet technique to produce the land and seascapes that would later define Ross's style. Indeed, the Zen-like positivity and wet-on-wet painting styles so commonly associated with Ross all originated with Alexander, who seemed to invent them sometime between his release from prison and his appearance in California. Alexander spoke of "happy trees" and "almighty brushes." With a soft, German voice he gave simple advice only superficially concerned with painting. "Let the sun shine in," he said while painting a dense forest. "Open up your heart and let the sun in." As Anderson put it, "It's not just what he was painting. It's what he was saying in between. About life. He was a philosopher."

Though he is far less widely remembered than Ross today, Alexander was, in his time, a national celebrity in his own right. He appeared on The Tonight Show, won a local Emmy and had his show syndicated in Canada and Mexico. According to Anderson, he was recognized everywhere he went. "We'd walk through the airport and people would just stop." On one such trip, Alexander asked an attendant how long the flight would take. Recognizing the Happy Painter, Anderson recalls, "she said, 'Mr. Alexander, you could paint four paintings on this flight.'" Meanwhile Alexander's books and videos sold millions of copies in the early 1980s, before he decided to retire.

One early follower of Alexander had been Ross, who was living in Alaska when The Magic of Oil Painting began, working in the Air Force. Ross was, by Kowalski's account, a solitary man. As Ross would later tell the Sentinel, his job in the military required him "to be a mean, tough person. And I was fed up with it. I promised myself that if I ever got away from it, it wasn't going to be that way anymore."

When Ross saw Alexander's show, he began to adopt the technique, eventually training with the Happy Painter. Soon he was making a living wage off his landscapes. "I used to go home at lunch and do a couple while I had my sandwich. I'd take them back that afternoon and sell them.'' He retired from the Air Force and began painting full time. Eventually, he and his wife moved back to Florida and began teaching seminars in the all-purpose rooms of hotels.

It is difficult to say why exactly Ross decided to teach painting. According to Kowalski, Ross was a rather solitary individual. "That Bob you see on TV is not all of Bob," she says. "There are other Bobs you don't know about." According to her, "He liked animals more than people." He once said, "If you study my paintings, there are no signs of human life." Apparently, she claims, he didn't paint chimney smoke coming from cabins in his landscapes because it would indicate humans were living there. Still, he felt a lot of compassion for other people, Kowalski says. "He wanted to solve their problems."

One of Ross's students was Kowalski, his future business partner. At the time, in the early 1980s, Kowalski was living in Washington, D.C., with her husband, Walter. A year earlier, the couple had lost their 24-year-old son in a car accident. "I had just lost a child, and I was very depressed," she says. Kowalski had seen Alexander's show on television and hoped to take a class with him, sensing the therapeutic quality of his philosophical approach to landscape painting. But when she contacted Alexander, she discovered he had retired. The Happy Painter suggested that instead she get in touch with a then unknown artist named Bob Ross. She went to Florida and attended Ross's class.

"The first day I realized the effect Bob was having on people," she says. Impressed by the painter's uncanny ability to soothe his students, she and Walter offered to financially back him. In 1982, they found a local station in Virginia to produce Ross's show. A year later, they were lured away by WIPB in Indiana, which promised Ross total creative control. At WIPB, Ross went on to record 403 episodes of The Joy of Painting. It was broadcast on 95 percent of all public television channels in America, putting Ross in almost 100 million households weekly and, later, on the monitors of millions of ASMR viewers via video-streaming sites like YouTube.

"Now," Kowalski says, "Bob Ross is all over the world."

CRAZY TINGLES

Among those viewers of Ross was Ilse Blansert, the ASMR artist who created the calculator video, along more than 300 hundred other videos, like "Gift Wrapping with Tape/Scissors & Crinkly Paper" and "Caring Role Play"—which is, essentially, a Bob Ross video without the illusion that anyone is trying to learn how to paint a forest stream. According to Blansert, one of her first childhood experiences with what she now calls ASMR came from Ross, when she was growing up in the Netherlands. "He only had 25 minutes an episode, but he never seemed to be in a rush. I would always feel these crazy tingles. The whole vibe of that guy is amazing."

Throughout her youth, Blansert continued to turn to Ross and other ASMR triggers—as when her grandmother would tell her stories at night, or when she would play telephone in school—for comfort in difficult times. "My mom dumped me on the street with all my stuff," she says. "My dad kind of saved me." Unfortunately, her father became sick and, when she was 16, died. All this trauma endowed Blansert with a certain amount of anxiety and unhappiness that, for years, she was unable to shake. "If you don't get the love you need, it leaves a lot of scars," she says. She soon developed an eating disorder and began suffering from depression.

All of this began to change in 2010 when, she recalls, she began searching for "relaxing videos" and discovered the ASMR community. Soon, her depression and eating disorder ended, and she began making videos of her own. "I've always been a loving person," she says. Maybe that's because of my dad. That's something I'll never know. But I always wanted to help people."

And she goes to great lengths to do so, taking video requests from loyal users. These requests, she says, can occasionally get rather strange. For example, she recalls one user asking her, "Can you pretend you are the size of a garden gnome and are being swallowed by someone? Can you talk about what it's like?" She declined. "I used to have a list where I saved all my weird requests," she says, "but then I realized how weird it was to save a list of all my weird requests."

Today, Blansert has more than 130,000 loyal subscribers to her YouTube channel. And, in total, her videos have been viewed more than 22 million times. Much of her audience, she says, is made up of "a lot of people with stress and anxiety. There is also a group of people who are sick and extremely traumatized." Indeed, many of the people Newsweek spoke to in the ASMR community suffered from PTSD, depression, trauma, insomnia and anxiety that, for one reason or another, seems to be relieved—or at least temporarily stifled—by the completely uncynical sincerity in videos of nice people speaking softly while doing nothing in particular.

Everyone has his or her own thing. Some like the sound of straws or chess pieces being shuffled in front of a three-dimensional microphone. Others want to pretend they are getting a haircut or an ear exam. But, she says, everyone watches Bob Ross. "To be honest with you, every video of Bob Ross is my favorite video."

So what is it about ASMR that appeals to so many people? As Blansert explains, "The world is moving so fast. A lot of people can't really find their way." For whatever reason, the soothing noises linked to ASMR that Ross seemed to tap somehow accomplishes this.

"I think a lot of people go to Bob because they are trying to get over some grief. They get over their depression, their life takes meaning," says Kowalski. "If you think all of that spine tingling is by accident, it's not. He told me he would lay in bed at night and plan every word. He knew exactly what he was doing."

Needham recalls a story of an encounter Ross had with one of his fans: "I remember a woman coming in one night to the building. This woman came to the front steps. She said, 'I just had to have this painting.' She grabbed his hands and started crying. 'I want you to know that I'm in constant pain. But when I watch you, I can relax.'"

In some sense, using ASMR to explain the popularity of Bob Ross doesn't get you very far. As of yet, only one functional magnetic resonance imaging study has been conducted on the phenomenon. The researcher, an undergraduate college student, showed subjects ASMR videos while observing their brain activity with an MRI. The results of the test have yet to be released, however. And so it cannot be said with any scientific certainty that ASMR even exists, or that a pair of local-access painters somehow tapped into it.

Needham, who believes working with Ross on the Joy of Painting was the most important thing he has done in his professional life, understands Ross's unlikely success in simpler terms. "He gave people a chance to have control over a small part of their world," he says. For all the schmaltz and predictability one might be inclined to find in such personalities, their appeal, like that of the ASMR artists, seems to come from a sort of hard-earned sincerity. One gets a sense, watching Ross or Alexander or Blansert, that these people are coming not from a place of self-help cliché but from having indulged in the temptations of cynicism, exhausting them, and deciding to just get on with things. As Alexander was fond of saying, "We're in the happiness business."