I remember that first year after I’d left the Jehovah’s Witness faith. I don’t think I’ve ever seen my mum cry so much, so often. She was convinced she’d lost me and that I’d be changed for ever now, no longer the daughter she’d always loved and cherished. “Mum, I haven’t died. I’m still here, and I’m still the same. You don’t need to mourn me,” I told her once.

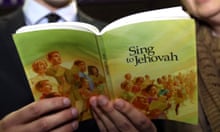

But it’s a way of thinking that is ingrained in you by the faith, and it’s this mentality that makes it so difficult to leave. You’re taught by the organisation that once you leave you will become corrupted by the outside world and inevitably descend into selfishness, meanness and false happiness. A life of meaningless sex, drugs and alcohol is often woven into this picture.

It’s this picture of the “world” – the word they use to refer to anything outside the faith – that was painted for me as a child, and I was warned away from cultivating any close friendships with non-Jehovah’s Witnesses for this reason. As a result, most young Witnesses grow up sequestered in their homes and their congregations, fearful of anything outside those boundaries. If at any point you do have doubts and want to leave, your forced isolation up to that point makes the decision inevitably intimidating and potentially overwhelming because of the prospect of being alone and without a support network to guide you through the process.

I was lucky enough to have parents who brought me up more loosely than most Jehovah’s Witnesses. I was allowed to make friends with people outside my congregation. It was these friends who became my support network and showed me that people from the “world” are just the same as people from the faith – there were as many lovely people as there were horrible people, as many happy people as there were sad. Being a Witness and following the doctrines didn’t automatically mark you as different or better than anyone else. I’d been treated badly by as many people who were Witnesses as I had non-Witnesses.

I was also lucky that both my parents encouraged me to get a good education – to work hard at school so I could go to university if I wanted. The faith discourages more than the bare minimum education, advising that higher education is a waste of time that could be better dedicated to “ministry” (a practice that is deemed so important every individual is required to submit a “report card” of the amount of hours they’ve spent preaching each month), and that it fosters a materialistic and selfishly ambitious attitude.

Realistically, though, it’s a threat to the organisation because education could broaden an individual’s mind and open them up to a world of opinions outside the faith. It’s the reason they emphasise the dangers and repercussions of searching for answers to faith-related questions in any place except their own literature, calling anything outside this “apostasy”. I’m grateful every day for my education and my desire to learn and think independently, a skill that fostered in me those initial doubts about Jehovah’s Witnesses, and enabled me to have the strength to search for answers elsewhere in non-biased literature.

I eventually left the faith at 18. Many former “friends”, including my best friend of 10 years, shunned me. Several people tried to convince me to return to the “truth” – the term they use to refer to anyone in the faith. I made a concentrated effort to stop using the word, because I knew it wasn’t the truth to me, and that its use was just a very 1984 Newspeak method of subtle control. I tried at all costs to avoid any discussions of faith with Jehovah’s Witnesses with whom I was still in contact – mostly because I didn’t want to be forced into an argument with them over my anger and frustration at some of the doctrines.

More than that, though, it infuriated me the way my most important reason for leaving was brushed aside because it was the most irrefutable: I simply did not believe in the Bible and God, and by extension any Christian belief. While I tried to maintain the utmost respect for their beliefs and not attempt to preach my own, they refused to extend me the same courtesy, and many assumed I’d left so I could experience more freedom for “worldly” things.

Leaving the faith at 18 changed my life completely. I went to university, where I made even more friends who showed me that being in the “world” is completely fine, and that debate and discussion is also OK. I began a life where constantly questioning and improving my beliefs and ideas and always being open to those of others were my only constant doctrines. I began a life where I could decide what to believe for myself, and I wasn’t afraid of someone telling me I couldn’t.