Had Katsushika Hokusai died when he was struck by lightning at the age of 50 in 1810, he would be remembered as a popular artist of the ukiyo-e, or “floating world” school of Japanese art, but hardly the great figure we know today. His late blooming (the subject of an exhibition, Hokusai: Beyond the Great Wave, opening at the British Museum next week) was spectacular – it was only in his 70s that he made his most celebrated print series, Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, including the famous Great Wave, an image that subsequently swept over the world. “Until the age of 70,” he once wrote (self-consciously parodying Confucius) “nothing that I drew was worthy of notice.”

It was a good boast but not quite true – he had begun his manga, woodblock print books of sketches that were wildly popular, in his 50s. They stretched to 15 volumes (the last three published posthumously), and covered every subject imaginable: real and imaginary figures and animals, plants and natural scenes, landscapes and seascapes, dragons, poets and deities combined together in a way that defies all attempts to weave a story around them. Leafing through the manga in the original or a facsimile is a mind-expanding experience, one that should be prescribed for all aspiring artists. In their observation and invention they have been compared to Rembrandt and Van Gogh, and rightly so for the thrilling panorama they provide both of the world and of Hokusai’s imagination.

If the manga made Hokusai’s name, the Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (there are in fact 46 prints in the series) ensured his fame. Hokusai’s obsession with Mount Fuji was part of his hankering after artistic immortality – in Buddhist and Daoist tradition, Fuji was thought to hold the secret of immortality, as one popular interpretation of its names suggests: “Fu-shi” (“not death”). I saw the mountain for the first time last year, from the window of the Shinkansen bullet train. You quickly understand how it dominates the landscape, as the train curves around, revealing it over woodlands and cities, behind buildings, over the plains – and why Hokusai returned to it so often, like a pivot for his restless imagination.

Fuji appears in Thirty-Six Views in many different guises, sometimes centre-stage, elsewhere as background detail. The first five in the series were printed entirely in shades of blue (a combination of traditional indigo and Prussian blue, a recently invented chemical pigment), suggesting views of the mountain at dawn, seen now from a beach, now from a neighbouring island, now as passenger boats and cargo vessels head out over Edo bay.

Hokusai gradually introduced colour into the series, delicate pinks and darker shadows, to show the illumination of the world as the sun creeps up over the horizon. The print Ejiri, Suruga Province shows early morning on a desolate patch of the Tōkaidō highway, Mount Fuji drawn with a single line, while in the foreground a group of travellers are struck by a gust of wind that sends hats and papers flying in the air. It is one of my favourite of the Thirty-Six Views. In Japan the best-loved print is Clear Day with a Southern Breeze. Included in the British Museum exhibition, an early impression of this print shows the delicate atmospheric effects of sunrise, lost in later printings probably made without Hokusai’s direct supervision.

Early impressions of the Great Wave, or Under the Wave off Kanagawa, are just as subtle in their colouring: atmospheric pink and grey in the sky, deep Prussian blue in the folds of the sea. Fishing skiffs are lost in the waves, while the great wall of water, with its finger-like tendrils, threatens to engulf both them and the tiny Mount Fuji in the distance. That the Great Wave became the best known print in the west was in large part due to Hokusai’s formative experience of European art.

Prints from early in his career show him attempting, rather awkwardly, to apply the lesson of mathematical perspective, learnt from European prints brought into Japan by Dutch traders. By the time of Under the Wave, the sense of deep space was far more subtle. The rigid converging lines of European perspective drawing become the gently sloping sides of the sacred mountain. In all other ways it could not have been further from anything being made in Europe at the time.

I would love to see an impression of Hokusai’s delicately coloured print hung next to Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa, painted just over a decade previously, in which a similar large wave is about to crash down on frail humanity. The contrast, and extreme modernity of Hokusai’s print, was certainly on the mind of those post-impressionist painters who so admired his work. You can still see prints by Hokusai, alongside Utamaro and Hiroshige, lining Monet’s dining room at Giverny; Rodin and Van Gogh were also enthusiastic collectors.

Hokusai signed his Thirty-Six Views with the name Iitsu, adding for clarification that he was “the former Hokusai”. It was common in Japan, as in China, for artists to adopt different names throughout their careers, marking different stages of life, and perhaps also as a way of refreshing the brand. He adopted the name Hokusai (“North Studio”) in his late 40s, when he became an independent artist, leaving his teaching job and striking out on his own.

By the time he created his second great tribute to Mount Fuji, three volumes comprising One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji (in fact there were 102 views) he was using the artist names Gakyō rōjin (“Old Man Crazy to Paint”), and Manji (“Ten Thousand Things”, or “Everything”). There is indeed a spirit of crazy comprehensiveness to One Hundred Views, all the mad invention and curiosity of the manga combined with the exquisite technique of the Thirty-Six Views. Timothy Clark, the curator of the British Museum exhibition, describes One Hundred Views as “one of the greatest illustrated books” ever printed, and it is difficult to disagree. The drawings are brilliantly conceived, and the prints beautifully made, the woodblock carvers reproducing Hokusai’s line so accurately that we think we are looking at the drawings themselves, rather than carved and printed copies.

It’s important to remember that Hokusai was a thoroughly commercial artist, relying on a large turnover of sales of his low-cost prints and the many illustrated books he produced throughout his life. Despite his artistic success, he seems to have been permanently on the brink of bankruptcy, largely a result of financial ineptness. After the death of his second wife, in 1828, Hokusai’s daughter, Katsushika Ōi, returned to live with her father and provided him with support. Ōi was herself a talented painter and worked alongside her father in their cramped and messy studio.

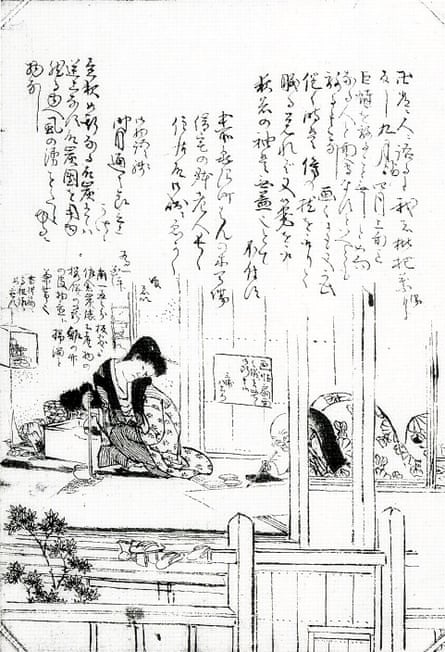

An image of their situation is preserved in a memory-sketch by Tsuyuki Kōshō, one of Hokusai’s pupils, showing the master in rented lodgings, covered by a quilt, hunched over an ink painting on the tatami mat. Ōi watches him intently, smoking a long tobacco pipe. An inscription on the drawing says that rubbish was piled in the corner of the studio, food wrappings and other detritus. On the wall hung a sign: “We strictly refuse to paint albums or fans” – although you can imagine them taking on the work anyway.

The small handful of Ōi’s paintings that survive show her prodigious talent as an artist. Recent research has shown how she might have contributed to her father’s late paintings, which contain elements of her style such as elongated fingers, and depictions of beautiful courtesans (drawn from life in the pleasure district of Yoshiwara, if the 2015 anime film Miss Hokusai is anything to go by).

One of her most impressive paintings, Hua Tuo Operating on the Arm of Guan Yu, a scene from the Chinese historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms, has a violent intensity and macabre quality quite unlike her father’s painting. Blood spurts from the arm of the general Guan Yu, who has taken nothing but a bowl of rice wine as anaesthetic, and continues with a game of go. It is one of the few authenticated paintings by Ōi, who disappears from the records following her father’s death in 1849.

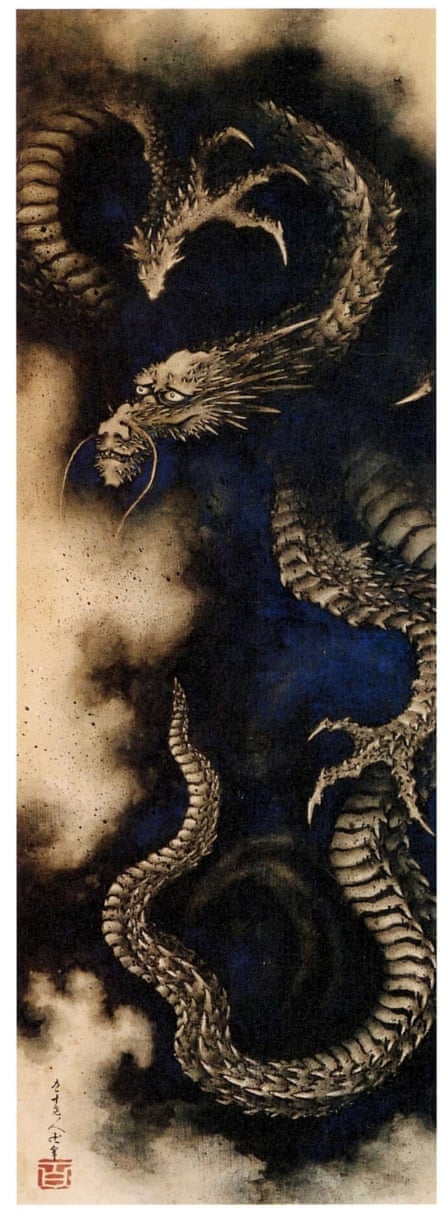

Set alongside his prints, Hokusai’s rarely exhibited late paintings – large hanging scrolls on silk and paper – strike a different note. The subjects are often fantastical: a great dragon writhes in a rain cloud rising above Mount Fuji; a seven-headed dragon deity flies in the sky above the monk Nichiren (Hokusai was a devout follower), sitting on a mountain top reading from a sutra scroll.

In small reproduction (the only form I have seen them in), they can appear a little like commercial illustrations, lacking the sense of emotional and atmospheric depth of his prints. A grinning tiger bounding through the snow, painted just a few months before Hokusai’s death, looks almost too quaint and jolly. All the more reason to make the journey to the British Museum and see them in the flesh. As with Hokusai’s prints, the real qualities of colour and surface, of detailed brushwork and painstaking construction, reveal themselves only on close and lingering inspection.

In his 80s, Hokusai was said to draw a Chinese lion or lion dancer every morning, throwing it out of the window to ward off ill luck. A number of these “daily exorcism” drawings still exist (probably thanks to Ōi running out to collect them up), and they are among his most lively and charming works. Hokusai’s only bad luck was to die 10 years short of his century, and never in his own mind to reach the state of artistic immortality, which he estimated would occur at the age of 110 when, as he once wrote, “Each dot, each line, will possess a life of its own.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion