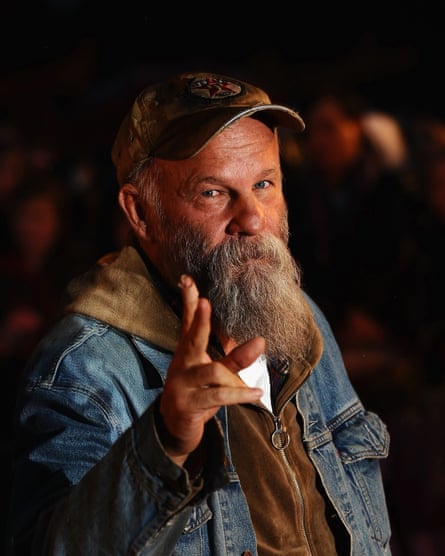

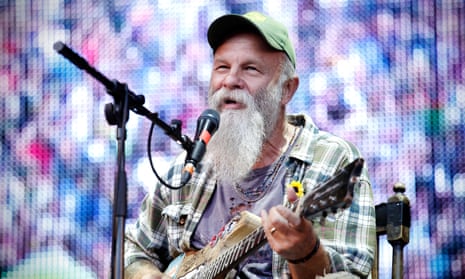

In 2007, Mojo gave its best breakthrough act award to a 66-year-old untutored blues player from Mississippi who built his own instrument from a cigar box and a spatula. At least it thought it did. In fact, it was giving it to a 56-year-old Californian session musician who had produced Modest Mouse’s debut album.

“Seasick” Steven Gene Wold’s late flowering of fame had always seemed quite remarkable. When writer Matthew Wright began work on a biography of the singer, who had built up a large and devoted cult following and won a Brit award nomination in 2009, he had expected to find periods of time that were hard to account for – Steve had been a hobo after all. Instead he found holes the size of craters, and they had nothing to do with his much-vaunted years wandering in the deep south. When Seasick Steve was meant to be rambling, playing the blues on his own three-string guitar, he had instead been cutting music of a very different stripe.

Steve claims to have been born in 1941, like Bob Dylan, Paul Simon and Joan Baez. His passport says he was born in 1951, making him a contemporary of Sting, Chris Rea and Bonnie Tyler. Wright dug out that Steve’s real name is Steve Leach, rather than the woodier-sounding Wold. The penny-dropping moment came for Wright when he discovered that in the early 70s, Steve Leach had played bass in a band called Shanti, devotees of transcendental meditation, whose sole album was reissued last year. At the time he was playing with Shanti, though, Steve had said he “was living and playing in Paris on the street in 1972. I was living in a park and it was real rough, and all that.”

It turns out that it wasn’t just his spell with Shanti that had been brushed under Seasick Steve’s carpet. He also played with a disco band called Crystal Grass, whose 1974 Crystal World single was a David Mancuso Loft classic, and was later sampled on Theme from S’Express. Leach/Wold may not have played on that particular single but he recorded an album – Dance Up a Storm – with them in 1976. The other players in Crystal Grass had a strong pedigree – Slim Pezin and Don Ray were part of the house band for Tele Music, France’s foremost music library, where French disco king Cerrone also cut his teeth. For disco and breaks fans, Steve Leach’s story has serious kudos.

There’s more. At the end of the 70s, he was singing backing vocals for Celebration, a Beach Boys splinter group put together by fellow Californian transcendental meditation advocate Mike Love. By 1982 he was a member of the splendidly named Clean Athletic and Talented (or CAT for short), writing and singing on their Woman and Sports album and their awkwardly titled single I Love to Touch Young Girls. CAT’s records appeared on the very cool Dutch disco label Rams Horn. By the late 1980s, he was a producer in Washington State, working with Modest Mouse among others, before he moved to Norway and reinvented himself after a bumpy boat ride.

So, with nothing to be ashamed about creatively, why would anyone be in denial of this career? Partly it might be because, during Steve’s disco years, he looked quite a lot more like Keith Lemon than a member of the Band. More likely, he twigged that people want romance from music. They want to believe someone’s artistic impulses are unfiltered. Seasick Steve got his break singing Dog House Boogie on Jools Holland’s Hootenanny in 2006, bashing his foot on what he called a “Mississippi drum machine”, which looked like an old car battery. He sang of “bumming around, living hand to mouth, sometimes goin’ cold and hungry … tryin’ to get your spare change.” “Yes!’ screamed Jools at the end of the song, with unusual, unguarded enthusiasm, “with a three string guitar! The genius from Mississippi!” Such a feel-good story. Seasick Steve, he gave hope to the homeless.

Hindsight’s a fine thing, but it’s hard to imagine how anyone fell for it in the first place. Maybe because he called himself Steve? Seasick Slim would have been a step too far, but Steve – not exactly a classic bluesman name – made it more believable. Evidence that Steve’s background wasn’t quite all it seemed has been hidden in plain sight all along. As Sean O’Hagan noted in an Observer piece, “The trajectory of his life since [1973] is hazy and, one suspects, he plays down the semi-settled years, sensing correctly that his mainly young audience prefer the myth to the reality”.

Steve admitted to O’Hagan he had stopped wandering in 1973, and had worked in the music business on and off since then, but he was only telling part of the truth: during his supposed wilderness years, Wright says, there had been brushes with Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix, among many others, and that he had lived in San Francisco continuously from 1965 to 1972. This was not a man on the margins, but the hobo myth played better to a gullible public. It was clear in interviews that Steve understood why people liked his gutbucket, ultra lo-fi music: “People are tired of everything being so fancy. There’s always been fancy music around and complicated shit” he sniffed in an uncomplicated way, and talked of how he dreamed about getting sponsorship from John Deere, or a whisky manufacturer.

So Seasick Steve is a fictional character. Does it matter, if the music is good?

In 2008, he told O’Hagan that he didn’t expect his fame to last but he’d like to “make some real money” while it does. Steve can market himself however he likes, but you have to admit that’s a less charming sentiment coming from a middle-aged man who has been a professional musician his whole life, rather than a self-educated, elderly hard-luck-hobo who says that when he has been settled he has largely worked blue-collar jobs.

Pop is all about self-invention, but there’s something uncomfortable about Steve’s version of it. Tom Waits’s act is clearly a performance, an exaggeration; he isn’t claiming to be a real alcoholic any more than Gary Numan tried to kid us he was a robot. Seasick Steve’s story is different. When asked what was most important to his songwriting, he said: “That it’s about something that happened to me, you’re digging up from your own mud. All my memories is like a train waiting to come into the station. It just has to be something real.”

There’s the nub of it. Steve Leach was a session musician; no digging around in his own mud was necessary. He was capable of playing blues, because he could play anything – that was his job. His unveiling reveals the sense of shame attached to session players, musicians who basically clock in, play, get paid and go home. There shouldn’t be, of course – great records from Good Vibrations to Unfinished Sympathy couldn’t have existed without session musicians – but it’s the least romantic job in music, the office job of pop. It suggests the exact opposite of the romantic ideal Steve sought to invoke; a breadhead who can turn their hand to any type of music on a whim.

If nothing else, the Seasick Steve saga has taught us one thing – if you’re going to lie about your age, add 10 years. People will never stop telling you how great you look.

- Seasick Steve: Ramblin’ Man by Matthew Wright is published by Music Press Books.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion