Every so often, the fallibility of scientific institutions is pushed into the spotlight. Recently, that spotlight has been focused on the retraction of a Science paper because one of its authors allegedly faked groundbreaking evidence that someone's political opinions could be changed by a short conversation with an affected person—specifically, in this case, that a conversation with a gay canvasser could persuade people to be more in favour of gay marriage.

This case has brought public scrutiny to issues of research ethics and transparency. In scientific communities, potential solutions to these problems have been debated and trialled for a considerable amount of time. The latest issue of Science includes three articles that lay out options for journals, universities, and individual researchers who hope to improve transparency and accountability in research.

You can't repeat what you can't see

Reproducibility is one of the cornerstones of science. If one lab tries something and finds that it works, but five other labs try it and come up with nothing, that’s an indication that something was strange about the first group’s results—perhaps they faked the data, or perhaps, more innocuously, they just did something differently.

To achieve accurate replication, each group needs to know exactly what other groups have done, so that any differences in the results can be properly understood. That’s where transparency comes in: too much important information in science—from the exact methods used, to the data they produced and how the analyses were conducted—never sees the light of day. In many cases, whole experiments are never published if they don’t produce any interesting results, leading to everyone having an incomplete picture of the available evidence.

“Transparency is central to improving reproducibility, but it is expensive and time-consuming,” writes Stuart Buck in one of the editorials. “Most scientists aspire to transparency, but if being transparent taps into scarce grant money and requires extra work, it is unlikely that scientists will be able to live up to their own cherished values.”

Part of what’s needed, write biochemist Bruce Alberts and a string of co-authors, is a change of incentives. “Researchers are encouraged to publish novel, positive results and to warehouse negative findings.” Terms like “retraction” and “conflict of interest” also carry negative stigma that aren’t always deserved, they write.

As long as “retraction” is associated with fraud, researchers will be wary of retracting papers for worthy reasons, like finding an error in the data they hadn’t known about before. Similarly, not all conflicts of interest are “corruptive,” the researchers suggest. If we adopt terms like “voluntary withdrawal” and “disclosure of relevant relationships,” these admirable behaviours could be congratulated, making scientists more likely to engage in them, the authors argue.

Journals need to lead the way

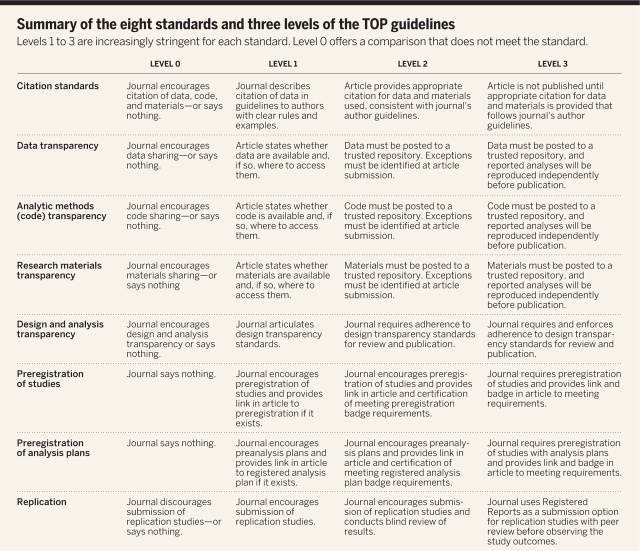

Psychologist Brian Nosek and numerous co-authors, writing in the same issue of Science, propose a robust framework that can be adopted by journals to improve transparency and replication efforts. Recognising that everything can’t change overnight, they suggest a graded system that allows journals to slowly make changes to their policies, starting with reward systems for transparent research, and finally reaching a point where these behaviours are required.

Pre-registration of experiments is one of the ideas that is often highlighted in debates about research ethics. It’s a practice designed to stop the problem of scientists burying neutral or negative results in a file cabinet. Pre-registration asks researchers to publicly announce the fact that they plan to conduct a study before they begin. They first publish their question and intended methods, and then after the experiment, the results get published no matter what they found—even if the results aren't especially interesting.

Some journals reward pre-registration with small incentives like “badges” on the resulting papers, but it’s a practice that hasn’t yet become mainstream. Journals operating at the highest level of the framework set out by Nosek and his colleagues would require pre-registration of studies.

It's much easier to replicate experiments and catch fraud if you have access to the original data. Some journals currently reward researchers for sharing the data that they used in an experiment. In the highest level of this new framework, data sharing would not only become compulsory, but independent analysts would conduct the same tests on it as those reported by the researchers, to see whether they get the same results.

So far, 114 journals have joined as signatories to these suggestions, called the Transparency and Openness Promotion (TOP) Guidelines. Being a signatory means that a journal has committed to reviewing its policies within a year, assessing where these guidelines can be worked in. That’s a flimsy commitment; journals could get away with very little change by adopting only a few of the guidelines, and choosing only the easiest to implement.

But self-interest may push them to do more, however. Journals do have their own incentives to promote research transparency—for one thing, better research practices would make it easier to spot problems before publication.

“The present version of the guidelines is not the last word on standards for openness in science,” write Nosek and his co-authors. This is only the first version; to ensure that the policies they recommend are both practical and effective, they plan to keep reviewing their suggestions as more evidence emerges—as all good researchers should.

Science, 2015. DOI: 10.1126/science.aab2374 (About DOIs).

Listing image by University of Michigan School of Natural Resources and Environment

reader comments

60