When Big Data Meets the Blackboard

Do the benefits of student analytics outweigh concerns over individuals’ privacy?

The recent debate over the NSA’s surveillance policies shows just how much Americans care about privacy—perhaps on an unprecedented scale. “This is the power of an informed public,” Edward Snowden wrote of Congress’s decision this month to limit the agency’s data-collecting power. “With each court victory, with every change in the law, we demonstrate facts are more convincing than fear.”

But when it comes to the future of education in the United States, what if Americans’ privacy concerns are hindering the constructive use of data, from customized student learning to better teaching performance? That’s the tension behind a growing body of education research by private companies, academics, and nonprofits alike.

McKinsey’s Education Practice, for one, published an article in April that considered the pros and cons of data in schools. Citing an earlier McKinsey report, the authors argued that using student data could feed between $900 billion and $1.2 trillion into the global economy each year. More than $300 billion of that value could result from improved teaching, while other benefits could arise from more efficiently matching students to jobs and programs, estimating education costs, and allocating resources to schools, according to the report.

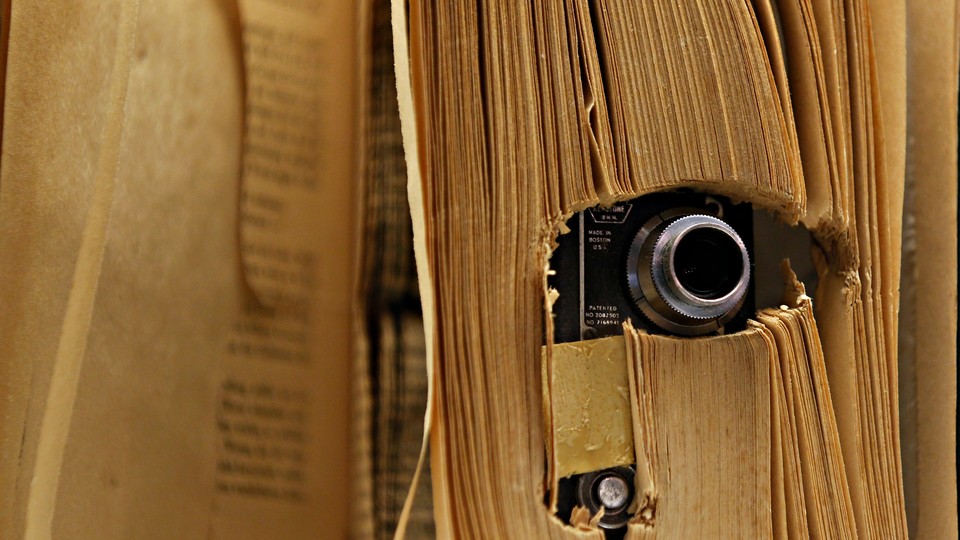

Still, many are skeptical, fearing that student data could be used inappropriately, or for corporate purposes. As Sophie Quinton reported for National Journal, analytics have raised ethical questions on college campuses, including whether institutions are essentially surveilling their students. One study from 2012 focusing on the higher-ed sector found that nearly a quarter of education professionals surveyed were concerned about the misuse of data, regulations governing data use, and individuals’ privacy rights. But when asked about data’s potential to maximize strategic outcomes, from student progress to efficient spending, more than 80 percent of the respondents said analytics would become more important in the future.

Similar concerns exist in K-12 schools. “Even if they don’t follow education policy, people’s ears perk up when they hear something about their own children’s data, and they can get swayed pretty quickly by groups that are fighting to maintain privacy at all costs,” says Rod Berger, the vice president of education at RANDA Solutions, a software firm based in Tennessee.

K–12 schools have almost always kept track of standardized test scores and graduation rates, but only over the past decade or so have they had access to more-detailed information captured by sophisticated analytic software. This level of tracking has caused some consternation among families. Last year, a nonprofit company called inBloom, funded by $100 million in seed money from the Gates and Carnegie Foundations, shut down because parents worried that their children’s personal information—stored by inBloom to help improve academic performance in public schools across the country—could be misused, sold, or breached. InBloom recorded student grades and attendance in addition to details like family composition, free-lunch eligibility, and reasons for enrollment changes, including medical conditions. It was one of an increasing number of third-party vendors that create, license, and implement education software—an $8 billion market, by recent estimates.

Reluctance to adopt data analytics across school districts may be preventing improvements to student outcomes and teacher effectiveness, according to Jimmy Sarakatsannis, one of the McKinsey article’s authors. He says parents are understandably concerned that decisions based on data could “rob the human experience from teaching and learning.” But, as a former public-school teacher in Washington, D.C., Sarakatsannis adds that most teachers strive for “personalization,” or instruction tailored to a student at a given point in time; data could help them achieve this goal.

Major textbook publishers like McGraw-Hill as well as smaller ventures like ThinkCERCA, a digital package of tools and lesson plans focused on boosting literacy, have already begun to capitalize on student data—proving that making kids smarter is smart business. The public’s concerns about privacy put a significant burden on these companies—and other stakeholders, such as policymakers to school administrators—to illustrate the benefits, says Ryan Baker, an associate professor at Columbia University’s Teachers College. One way to do this, Baker says, is by measuring engagement: to what extent a student expresses interest in and motivation to learn about a particular subject. (Although experts disagree over what the term exactly means, “engagement” can typically be measured by surveying students and teachers and by observing classroom behavior.) Baker adds that tracking such data can help teachers identify which kids are struggling with which material.

Of course, not all students enjoy the same subjects: a bookworm may find calculus impenetrable, while a math whiz may think history is boring. That largely leaves it up to teachers to encourage their students to go beyond their comfort zones, says Eileen Murphy Buckley, the founder and CEO of ThinkCERCA. Her company, which emphasizes the role of debate and collaboration skills in education, provides teachers and school officials with data dashboards that display an individual student’s progress. But having sophisticated information about students isn’t a cure-all for education’s challenges, Buckley notes.

“There’s this dream that we will have data that will make everything adaptive, and that thinking humans won’t have to do anything anymore,” she says. “I’m not there—it’s like thinking you could successfully automate a sales force. Even if you’re doing a lot of data-tracking, you still need a thinking human to interpret it.”

Reasoning Mind, a Houston-based nonprofit, does with math what ThinkCERCA does with literacy: It offers an online platform to help students advance their computational skills. George Khachatryan, the cofounder and a senior executive of the organization, says Reasoning Mind collaborates with teachers and even math Ph.D.s (called “knowledge engineers”) to develop curricula. It currently serves over 100,000 students in grades two through six, 85 percent of whom reside in Texas. Khachatryan argues that the platform has reduced student boredom, increased standardized test scores, and allowed teachers to give students targeted feedback, citing research studies the company has conducted with parental consent. “It permits a better allocation of human time,” he says.

Administrators can leverage student data to more fairly distribute financial resources, too. This could go a long way towards making American education more equitable across demographic groups: Under the status quo, public-school funding is regressive in many states, with schools serving disproportionate numbers of low-income students receiving fewer resources. As Susan Dynarski recently wrote in The New York Times, researchers and others rely on data to “pinpoint where poor, nonwhite, and non-English-speaking children have been educated inadequately.” Student data, in other words, could help make education the “great equalizer” it’s supposed to be.

Various obstacles, including political ones, stand in the way of that vision. The public’s aversion to data-gathering—exacerbated in part by the current discourse surrounding national security and privacy—may threaten to stymie new education research. According to the Pew Research Center, more than half of Americans (54 percent) disapprove of the government collecting individuals’ phone and internet data to combat terrorism. Education may be quite different from national security, but American attitudes on privacy and personal data suffuse both.

Jose Ferreira, the founder and CEO of Knewton, a New York-based company that develops adaptive-learning tools, says a lot of student data is going to waste right now; rather than being forgotten at the end of each school year or semester, it could be harnessed responsibly to drive learning outcomes. His company tracks students’ proficiencies across a variety of subjects, but will not share that information—even with teachers—unless explicitly authorized to do so by a student’s legal guardians.

“If you’re going to touch people’s data, it’s very important that the benefits be clear,” he explains. “‘Why should I let you collect my data? The benefits are fantastic? Now you have to reassure me you’re going to use it in a way I’m comfortable with.’”