Antennas are usually metal, but it turns out that saltwater is actually a decent conductor of electricity. Its conductive properties are minimal when compared to most metals, but at about 1,000 times more conductive than tap water, it's good enough to transmit and receive radio signals. (You can set up a DIY circuit using seawater as a home experiment.)

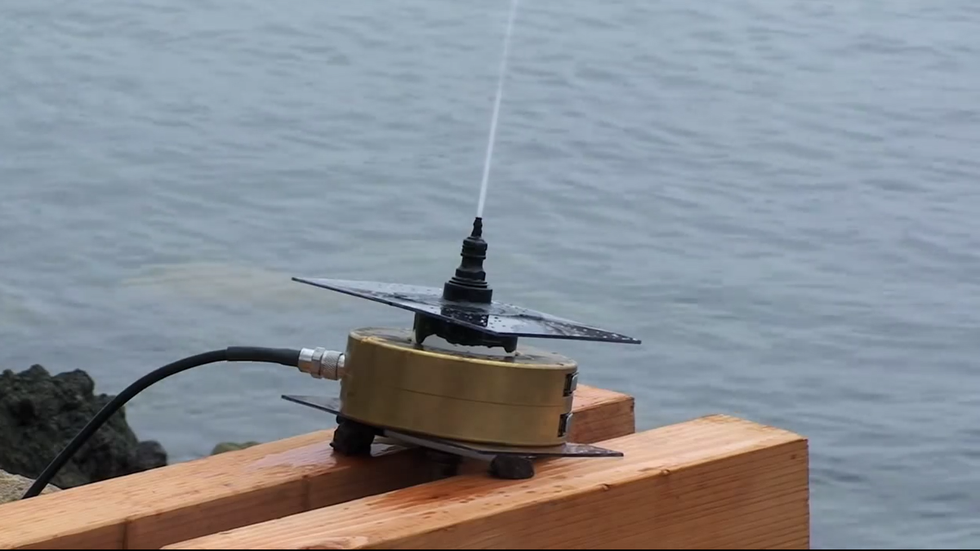

When saltwater is pumped through an insulated nozzle to create a tight water jet flowing up toward the sky, that stream is what makes the antenna. After some fine-tuning, Mitsubishi Electric was able to figure out the best diameter for their SeaAerial saltwater antenna, one that game it 70 percent efficiency, which is enough to transmit and receive signals. In a proof-of-concept test, a small antenna made of seawater (hardly bigger than the stream of water from a drinking fountain) was able to reliably pick up TV signals.

Mitsubishi claims theirs is the first functioning seawater antenna, although the Navy has been experimenting with the tech for years. Understandably! Seawater antennas could prove useful to Navy vessels that use large antennas to broadcast very low frequency signals across huge distances. The large antennas make the ships easier to pick up on radar, so having a seawater antenna that you can switch on and off and easily move around could prove extremely useful.

Seawater antennas could also be used along the shore, or even on land if the water recycles like a fountain. Of course, weather and a number of other factors make it hard to create a reliable antenna from just water. Still, if the design can be perfected, you might see these things popping up along your favorite beach. Just think twice about what you might be disrupting if you run through one.

Source: Mitsubishi Electric via Gizmodo

Jay Bennett is the associate editor of PopularMechanics.com. He has also written for Smithsonian, Popular Science and Outside Magazine.